Details Are Part of Our Difference

Embracing the Evidence at Anheuser-Busch – Mid 1980s

529 Best Practices

David Booth on How to Choose an Advisor

The One Minute Audio Clip You Need to Hear

Category: Philosophy

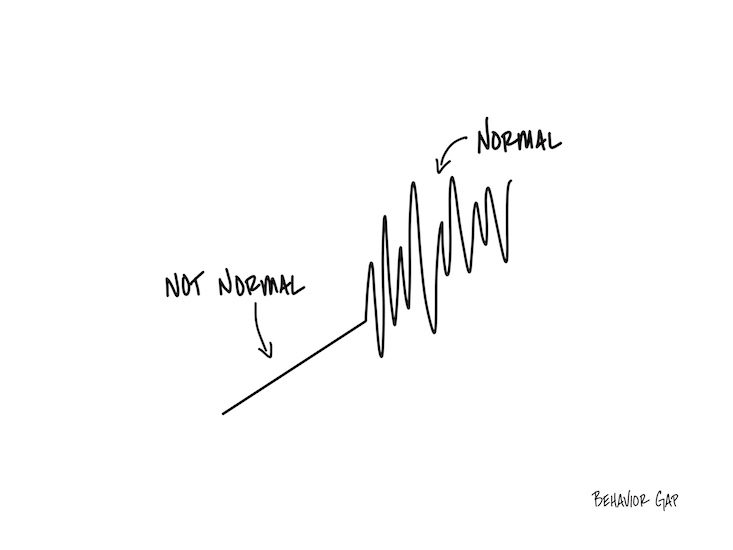

Normal Volatility

Imagine it’s a very still day, and you’re in a boat on the ocean.

There’s no wind.

No swell.

The water is as flat as a mirror.

The calm goes on just long enough for you to start to feel like it’s normal.

When a small wave finally comes… it feels big. When a regular wave comes… it feels huge.

As scary as it might feel, it’s important to remember that waves are normal.

In fact, occasional storms are normal.

And the last thing you want to do when you get into a storm is abandon ship.

Fishing & The Long View

Past podcast guest and avid fisherman David Coggins recently shared some thoughts on taking the long view in his newsletter, and it feels like you could swap “fishing” for “investing”, and the meaning might remain close to the same:

The Long View – People have a platonic vision of what fly fishing should be, and when they start, they feel like they’re a long way off. Then they get frustrated. I get it. There isn’t a fishing humiliation I haven’t suffered through—tangles, knots, catching the tree behind you, catching the same tree behind you again, falling in the water, losing a fish, losing more fish. That’s all fishing. But fishing is also: being on the water, engaging with the natural world, being in a beautiful place and not looking at your cell phone, and yes, drinking terrifically bad beer. Fishing, for me, is the entire experience and the small disasters along the way are part of the long game.

When I’m with a friend who’s learning to fish, and we get to the water, there’s always a sense of anticipation and a few nerves. I take a moment to say, “I’m happy to be here with you. Don’t worry about mistakes. I’ve made them all. We’re here to have a good time in this beautiful place. It’s going to be a good day.” And it is.

Giving With a Warm Hand

Have you listened to the latest episode of Take the Long View, our podcast that helps listeners reframe how they think about money, emotion, and time? We’ve had great guests over the years who have helped the podcast receive national recognition, but we especially enjoyed Matt Hall’s most recent conversation with Meir Statman.

Meir is a legend in the field of behavioral finance. He started thinking about how our emotions, biases, and beliefs affect our financial decisions way before it was a common topic. Meir was so far ahead of the curve, the university where he was teaching at the time worried that he was “corrupting” the minds of his students with crazy ideas. Today, he’s the Glenn Klimek Professor of Finance at Santa Clara University. He is recognized as one of the most influential thinkers in the investing world for his books and award-winning research papers.

The conversation touched on many issues related to the importance of taking the long view and putting the odds of long-term success on your side, but it also contained illuminating stories from his own life. Our favorite moment came when Matt asked him whether he sees any differences in the way people think about money in his home country of Israel versus the United States. He immediately offered a view of how families in Israel think about supporting their children financially.

We encourage you to listen for yourself (starting at 11:34 in the episode), but Meir describes a tendency he calls “giving with a warm hand, rather than a cold one.” Essentially, families in Israel emphasize supporting their children financially when it really matters — when they’re young adults who have just finished college or are getting married. As an example, he shared how his parents and his fiancée’s parents met before the wedding to discuss how much money each would contribute so the newlyweds could buy an apartment and start their life together from a solid foundation.

He contrasts that approach to the common tendency among American parents to hold off on giving money to their children early in life, often out of fear that they’ll somehow spoil them or make them work less hard for their own success. Instead, many parents plan to leave their assets to their children after they die, at which point the kids are probably going to be in their 60s and might not need as much support.

In Meir’s mind, this “cold hand” approach misses the value of giving young adults the resources they need to help them find their ambition. Freeing your children from some struggle and stress over money is like a long-term investment in their stability and happiness.

Later in the conversation, Meir emphasized this point by discussing the focus of his latest research—studying what investors really want. Yes, investors want to make money, but he notes that we should never forget what money is actually for. We want money for well-being, which is about family, security, happiness, health, and being true to our values.

We hope this idea sounds familiar because it’s central to the Hill Investment Group philosophy of building your financial plan to focus on what really matters to you. We take the time to listen and understand who you are, what you value, and what you hope to achieve so that we can put your money to work toward that vision and free you to focus on the important things in life.

For most of us, supporting and nurturing others is top of the list. So take a few minutes to listen to Matt’s recent conversation with Meir Statman, and then reach out if you’d like to discuss your giving strategy. We’re here to help you think through how you can fully support your values and beliefs while delivering the greatest long-term benefits to you and your family.