Details Are Part of Our Difference

Embracing the Evidence at Anheuser-Busch – Mid 1980s

529 Best Practices

David Booth on How to Choose an Advisor

The One Minute Audio Clip You Need to Hear

Category: Philosophy

Broken Clocks are Right Twice a Day

Does anyone know when to get in and out of the market? Many professionals try, and we’ve heard a few theories from amateur investors lately. It’s tricky to tell fact from fiction. There are a million ways to analyze historical data to find timing patterns that appear to produce attractive returns. The real question you need to ask yourself: “Is there any reason why I should expect that pattern to continue in the future, or is it purely due to chance?”

An example. Over the last thirty years, if you sorted stocks based on the letter of the alphabet they started with, you would see that stocks that began with the letter “M” outperformed those that started with the letter “E.” Is there any reason to suspect this to continue over the next 30 years?

No, clearly, the letter of the alphabet should have no impact on a company’s returns. The reason for this difference is that Microsoft was a large, successful company over this period, while Enron was a large, unsuccessful company over this period.

When working with “noisy” data, the odds that the results are evenly distributed is very small. If you roll a die six times, the odds of getting each number exactly once is tiny (1.5%). That means there is a 98.5% chance you will roll some number two or more times and some number zero times.

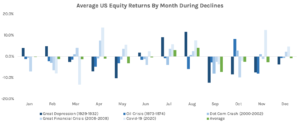

A typical market timing strategy we hear about around this time of year is to “avoid investing in the month of September.” At first thought, it seems odd that September would produce below-average returns, but when you look at the historical data, it is true!

Is there any economic rationale as to why this should continue in the future? I can’t think of any. Some claim that it is due to market participants selling positions to clean up their books after taking time off in the summer. If that were true, why wouldn’t investors try and get ahead of it and sell in August? Or why wouldn’t hedge funds gobble up all the low-priced stocks and keep prices stable?

Let’s dive deeper into the data and look at the five largest market declines over the last 100 years. Each drop produced several months of negative returns, but all five of them spanned September at some point.

The recession peaked in different months every time, and every month was hit negatively at some point. However, there was bound to be one month affected more than others. It just happened to be September. From 1926 to 2021, 52% of the September months had positive returns. The large negative returns from a few market downturns have skewed the average to be negative. The question is, do we expect this to continue in the future?

Whenever you hear of these market timing strategies, you need to ask yourself if there is a logical economic rationale as to why the trend existed in the past and why it should continue in the future. Is there some risk associated with September we don’t know about? Is there some behavioral rationale that investors can’t arbitrage away? If you can’t come up with a concrete reason, whatever anomaly you are looking at is most likely due to chance and not a reliable trading strategy to implement in the future. Before accepting any investment truism, it is important to be sufficiently skeptical before implementing it yourself.

Returns from Fama/French CRSP Data Library.

The Paradox Of The Herd

Clients and friends of Hill Investment Group will recognize the story behind “The Paradox Of The Herd” written by John Jennings because they are living it every day that they are Taking the Long View. John is the President and Chief Strategist of St. Louis Trust & Family Office, author of the blog Interesting Fact of the Day and forthcoming book titled The Uncertainty Solution: How to Invest with Confidence in the Face of the Unknown, and good friend of our firm.

The brief post discusses the emotional rollercoaster that those who invest differently than “the herd” ride, even though their rational selves know that doing so has a good chance of leading to higher expected long-term returns.

The good news is: You’re not alone. Everyone at Hill Investment Group is riding the same roller coaster as our clients because we invest our money the same way. (N.B. Everyone has their own asset allocation.)

ESG Investing and Should You Get Into It?

Many of us may have heard of one of the latest trends in investing – ESG. But what is ESG? Is it beneficial to your portfolio returns? This article will answer these questions from my perspective as the HIG 2022 Summer Intern. But first, what does it mean?

ESG stands for three different elements of a company’s operations:

- Environmental (factors affecting the climate and natural habitat)

- Social (factors affecting stakeholders like employees, suppliers, shareholders, and the society they operate in)

- Governance (the National and International regulators of the business)

ESG is essential to know about today because investors have increasingly started to apply certain non-financial factors when evaluating companies for investment.

ESG ratings attempt to assign a quantifiable value to a company depending on the impact the company has with respect to any of these three factors. Often measured on a scale of -100 to +100 – a positive score is intended to indicate a favorable impact, and a negative score is intended to indicate a potential risk in these areas.

For example, within the ESG matrix’s social governance sector, a company may be given a positive value for increasing diversity hiring in their workforce and assigned a negative value for having no/low female representation in their upper management. In the ESG thinking, sub-par Human Resource policies could lead to potential future lawsuits, theoretically reducing the company’s future expected return and share price.

An issue with these ratings is that things can get confusing quickly. Consider, what happens if Company X scores low on the social scale due to a lack of diversity hiring but performs high in the environmental segment by lowering carbon emissions. Let’s say that Company X comes out with an excellent overall ESG score. With a high ESG score on paper, investors might invest in this “good” company, not knowing that it is scoring high in Environmental but low in Social. In my opinion, investors can be easily confused by high ESG scores, investing while blind to unhighlighted risks.

Additional questions arise about investing in an ESG strategy because there is no standard way of calculating ESG scores. There are numerous rating agencies (MSCI, Sustainalytics, RepRisk, ISS, etc.) that assign ESG ratings to companies. Each of these agencies has a different formula and factor input data and related variables differently to arrive at their score. This means that companies on different rating scales cannot be compared with one another.

So how, as an investor, can you navigate the world of ESG investing?

Ratios like EPS (earnings per share) and EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation) are standardized. These measures are easy to calculate and to use when comparing companies. By contrast, ESG ratios are often opaque and time-consuming to calculate, and therefore, more expensive to apply. This can result in ESG Funds being comparatively expensive to most Index funds without any indication of higher overall performance. ESG funds, because they can remove entire segments of the market – for example, fossil fuels – are often less diversified than most index funds leading to a greater concentration of risk. This could lead to lower returns and higher volatility for the investor.

Because ESG is still a relatively new concept, relatively few funds in this segment have a track record of 20 years or more to judge them accurately. So, the question remains – what do investors do If they want healthy returns but still wish to help society? They may be hard-pressed to choose one over the other and feel they must compromise on either returns or activism.

For some investors, investing to create change brings them happiness and satisfaction rather than maximizing their investment returns. ESG investing may be perfect for them. However, investors hoping to meet or exceed market returns may be disappointed.

One compromise that may leave them satisfied would be to invest in a diversified manner and use some of their income or investment returns to donate directly to specific causes or charities where they want to make a difference. This could also lead to tax benefits for the investor through using a Donor Advised fund, and the potential for higher expected returns through lower investment costs.

Another option is to support society through non-monetary means like raising awareness through volunteer work, changing individual consumption, or directly supporting activists who champion change by joining their work and helping out in their agendas.

I hope that I have provided a better understanding and more clarity on ESG practices so that you can choose the investment philosophy that best suits you!

Please feel free to call us or book an appointment if you would like to further discuss this topic.