Details Are Part of Our Difference

Embracing the Evidence at Anheuser-Busch – Mid 1980s

529 Best Practices

David Booth on How to Choose an Advisor

The One Minute Audio Clip You Need to Hear

Author: Matt Zenz

2022 Investment Performance

It’s no secret that 2022 was challenging for both the stock and bond markets. Stocks ended the year down 18%*, while bonds were down 13%**. How did we do in 2022? Thanks to our compliance group, all we can say here is that our strategy of investing in low-cost, diversified strategies that tilt toward small, value, more profitable stocks meaningfully outperformed the S&P500 index in 2022.

As much as I would like to pat our firm on the back, you know our refrain: one year is essentially meaningless when it comes to investing. Due to the volatility and randomness of markets, any strategy can outperform or underperform in any given year. Our strategy certainly does not outperform every year and can even underperform several years in a row. To have real confidence in an investment strategy’s reliability, investors must look at how it performs over decades, not just years.

To see how we measure up over the long haul, we go back as far as we can, looking at the investments we recommended each year (and own ourselves) to see how our philosophy has held up over time. Our favorite chart compares the value of a hypothetical $1 invested in the year 2000 to 2022. Some of you may be familiar with Paul Harvey’s famous line regarding “the rest of the story.” Shoot me a note at zenz@hillinvestmentgroup.com for the details and the rest of the returns story. We can share how our recommended equity strategy has performed over time and the magnitude of the benefit of taking the long view.

If you have been a client for a while, you have likely seen the benefit of a long-term, evidence-based strategy show up in your portfolio. If you’re not a client, ask yourself why. Then pick up the phone and call us. You can schedule a call with me anytime here.

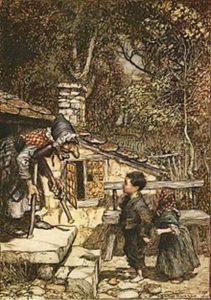

The Lure of Private Equity

One of the most memorable fairytales of my childhood was the story of Hansel and Gretel. In this tale, an evil witch lures two children to her house made of gingerbread with the promise of candy and sweets, only to try and eat the unsuspecting kids. This story was namely memorable due to the nightmares that it caused me, but I never forgot the lesson that if something sounds too good to be true, it probably is. Investing in Private Equity (PE) reminds me of this story. Private Equity managers lure investors in with the promise of exclusive access to uncorrelated returns and higher performance reserved only for the ultra-rich. One only needs to dive a little deeper to realize that many of these claims aren’t what they appear to be. Lack of pricing, misleading return numbers, high fees, and illiquidity make this asset class less than desirable.

|

Lack of Price Transparency | PE investments are only priced once a quarter. These prices do not come from actual trades between willing market participants, but rather from PE managers claiming what they think they could sell a business for. Only posting prices once a quarter, and not having transparency on where those prices came from, makes the returns of PE appear smoother and less risky than they truly are. |

|

Internal Rate of Return (IRR) | PE managers often advertise their stellar returns via IRR numbers. For example, firms like Apollo and KKR have since inception IRR returns of 25-35% a year! Who wouldn’t want to invest in a firm that has returned 30% a year for decades? Unfortunately, this IRR number is not comparable to the time-weighted returns you see from public markets. Early success on low asset values can skew the IRR number to look higher than the return most investors experienced. Based on the amount of assets Apollo and KKR have managed over the last few decades they would have 2.5x more assets than they currently do if they had 30% year-over-year returns since inception (not including any additional inflows from new clients). Using more comparable return calculations you find that PE returns are very similar to those of public markets. |

|

High Fees | All-in, PE fees are ~6-7%/year. This is made up of mostly a management fee and a performance fee. Management fees are usually around 2%, but some of the more successful managers charge even more. Performance fees are usually around 20%, charged on top of the ~2% management fee. As a point of comparison, the public equity funds we use in our models today charge between 0.17-0.39% management fees (8x cheaper), and no performance fees. Ultimately the economic rents of skilled PE managers accrue to the managers themselves, not the investors. PE is often referred to as the “Billionaire Factory” – for managers, not investors. From 2005 to 2020, 19 new billionaires came out of Private Equity alone. |

|

Illiquidity | PE also has the nasty feature of illiquidity. Once you decide to invest, your money might be tied up for 5-10 years, meaning you can’t get it out if you need it. This lack of flexibility is a large drawback to this style of investing. You may be willing to make this sacrifice for the prospect of higher returns. But as already discussed, because of the high fees there is little evidence that PE can reliably provide higher returns. |

This information is educational and does not intend to make an offer for the sale of any specific securities, investments, or strategies. Investments involve risk and, past performance is not indicative of future performance. Consult with a qualified financial adviser before implementing any investment strategy.

Grateful for Diversification

This year, I’m grateful for Diversification. Diversification is the only free lunch in investing. Let me repeat that. Diversification is the only free lunch in investing. As an investor, it allows you to dramatically reduce the range of possible outcomes in your investment portfolio, thereby making it easier to reach your financial goals. The range of performance of individual US companies this year was extremely wide and volatile. Think of it as a roller coaster with huge and frequent ups and downs. By diversifying, you were able to avoid some possible very negative outcomes. The video below provides a nice visual of the performance of the S&P500 year-to-date and gives an example of how increasing diversification, in this case by adding in small-cap companies, can help smooth the ride.

Video created by Jan Varsava.